Research, rankings and Brexit

What toll will Brexit ultimately take on UK universities and those who conduct research or study at them? As Forum Week continues, we look to some of the structural impacts of Brexit on dynamics like student mobility, research cooperation and rankings.

As most people know by now, Brexit constitutes a significant change in the UK’s position in the European Union, and more significantly, globally. At this stage in the story, it is difficult to know which path Brexit will take, but it is clear that Humpty Dumpty cannot easily be put back together. The UK will remain a member of the EHEA, but there is huge uncertainty about the UK’s future involvement in Erasmus and Horizon Europe programmes as well as other initiatives. Accordingly, universities, academics and students have already begun to make alternative arrangements for study abroad and other mobility opportunities and research partnerships. Anecdotal evidence suggests the UK has already been silently dropped off the list of preferred partners.

Countries are advising their universities and agencies to prepare for a ‘hard Brexit’, that being a scenario in which no deal with the EU is reached and everything stops immediately, at least for the immediate future.

What does all this mean for students and researchers?

Effects vary by country; Ireland, for example, has a historically strong relationship with the UK, despite pursuit of independence which came in 1922. There are extremely close ties with respect to academic and student mobility in both directions, and the UK has been the first job destination for Irish graduates. On 8 May 2019, the British and Irish governments agreed to maintain the Common Travel Area. This will continue to protect citizens of both countries to live and work freely. It will also facilitate associated rights and privileges for Irish citizens in the UK and British citizens in Ireland including the right to reside, to work, to study and to access social security benefits and health services, and to vote in local and national parliamentary elections.

In the meantime, Ireland, as well as other EU countries, is experiencing a Brexit bounce – attracting increased numbers of international/non-EU students and academics/researchers who might previously have considered going to the UK. This includes EU students pursuing a full-time undergraduate qualification. Ireland has the advantage of being English-speaking, but other EU countries with strong English-language programmes are also attractive.

The changed socio-political and cultural climate is a contributory factor. Brexit has ushered in an unpleasant environment of xenophobic nationalism alongside restrictions on immigration, which includes students. However, unlike the US, which has seen a 10% decline in international students 2016–2017, the UK remains a popular destination, especially for Chinese students.

While the Political Declaration between the UK and the EU provides for ongoing research activity based on “reciprocity”, a no-deal scenario calls this into doubt

Yet, in a no-deal Brexit scenario, all existing legal arrangements will expire unless alternative arrangements are in place. This will affect Erasmus and other mobility programmes. Issues may also arise with respect to recognition of some professional qualifications which fall within the remit of EU Directives, such as health and medical professions, pharmacists, architects, and veterinary surgeons. Qualifications regulated and recognised by the EU prior to 29 March 2019 will not be affected but are open to national decisions. There may also be consequences for accreditation of UK TNE provision in other EU countries.

Research is one of the most problematic areas. Horizon 2020 is due to end on 31 December 2020, while its successor, Horizon Europe, is currently being negotiated. While the Political Declaration negotiated between the UK and the EU provides for ongoing research activity based on “reciprocity”, a no-deal scenario calls all this into doubt. In such circumstances, the UK will become a third country and the UK government will be required to financially guarantee funding in circumstances where the UK economy is projected to continue to slow down. Tough negotiations between Switzerland and the EU provide a valuable message for the UK.

Brexit foreshadows bigger changes

When the UK joined the EU in 1973, the world economy looked very different to today. In the intervening decades, globalisation has transformed the economic as well as the higher education and research landscape. As the UK and US experience ongoing decline in their share of the global gross domestic product (GDP), other countries – notably China and India – are rising. World growth may be uneven, but it shows us that many more countries now participate in higher education and global science.

Rankings are inappropriate measures of quality, but they tell us something about the overall standing of universities based on research activity and reputation

Disentangling Brexit from these broader geopolitical changes can be tricky, but global rankings provide a clue. Rankings are highly inappropriate measures of quality, but they tell us something about the overall standing of countries and universities based on research activity and reputation. Rankings are a zero-sum game; as some universities rise, others fall. They are also a lag indicator, highlighting changes which have already occurred.

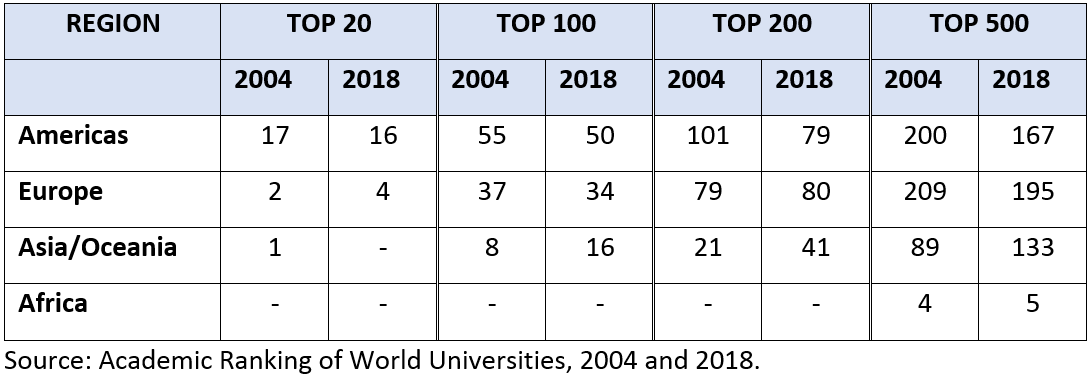

The UK has traditionally performed well in global rankings. In 2004, when the Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) was first published, the US and Europe dominated, with 179 universities listed among the top 200; by 2018, they held only 159 places. China had two universities in the top 200 compared with 19 for the UK and 90 for the US. By 2018, China has 15 universities in the top 200 compared with the UK’s 21 and the US’ 69 (Academic Rankings of World Universities, 2018). Table 1 below illustrates this change. This shift is also reflected in the recently-published 2019 QS World University Rankings, which assigns 50% of its total weighting to reputation.

Table 1. ARWU Distribution of Universities in Top 20 – Top 500 by World Region, 2004 and 2018

Brexit will accelerate these trends. Top-ranked UK universities are more likely to weather the storm, but regional and less prestigious universities are likely to face significant challenges. These challenges will intensify due to a decline in public funding for UK universities as proposed in the recently-published Review of post-18 education and funding.

Reputation can be a slow burn, but once lost, it’s hard to regain.