The future of student mobility: 3 scenarios

Within the international higher education (IHE) landscape, two of the (arguably) most significant impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been the devastation of student mobility and the ‘digital turn’ experienced by many. Continuing Forum Week and the launch of the Summer Forum issue on ‘Mobility in the balance’, this article looks at potential scenarios for the future of IHE in the coming years.

The pandemic has significantly disrupted international student mobility: a sector that was expected to experience between 5-8% growth between 2015 and 2025 has effectively been brought to zero as a result of successive lockdowns, difficulty in travel and closed borders, as well as nervousness to be trapped far from home. As shown by the EAIE New report: 2020–2021 student exchange mobility with non-EHEA partners , there are drops in both inward and outward flows of students between Europe and non-EHEA countries. Some countries have been completely closed to international students (Australia, New Zealand, China), with others encouraging distance enrolment (United States, Canada).

This has had a significant negative impact on university finances. International students’ fees provide a large and increasing share of providers’ total income and universities gain a surplus or ‘profit’ on teaching international students. This surplus helps to fund important ‘loss-making’ activities such as research, STEM teaching, investment in facilities and widening participation activities. In the UK, for example, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has estimated that the loss of international students will be the single biggest cause of losses to the income of higher education from the pandemic, forecasting these losses to be between £1.4 billion and £4.3 billion.

A slow pace of recovery for international student mobility may increase as the desire for in-person interactions and experiences abroad increases.

Then there are the many aspects of the rapid pivot of the sector to digital technology. During the pandemic, education provision throughout the world, at all levels, has been put on hold and delivery modes altered. The effects of this will be longstanding and will have a very human impact on skills, equality, economic productivity and income. A survey of 200 university leaders from around the world revealed satisfaction at how the transition to digital and interesting variations of this for different regions and audiences. However, this ‘digital turn’ also creates new opportunities to engage in international education through alternative means such as transnational education (TNE), with universities able to potentially leverage digital technology in the future to access a wider range of students, including international students. That said, there is growing conversation about the limitations of online learning, which cannot always or adequately replace in-person modes in some cases, with international exchange being particularly relevant to this.

Three possible futures

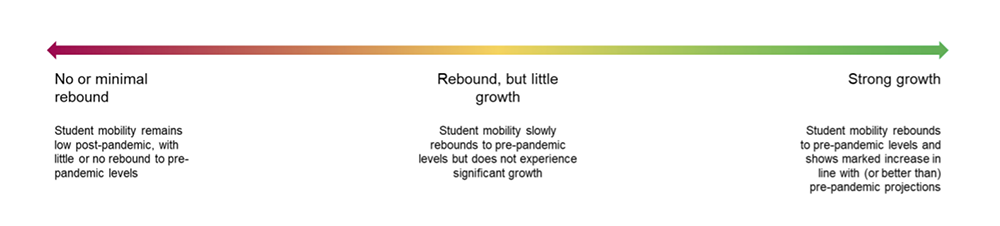

What are the future implications of all this? Looking at the ways in which COVID-19 has impacted the international higher education sector, there are a number of potential scenarios for the future of IHE in the coming years. These potential futures can be considered along a spectrum, from no meaningful rebound of student mobility to pre-pandemic levels through to rapid rebound and significant growth.

We consider three points on this spectrum as possible scenarios for the future:

1. Student mobility doesn’t rebound.

There is a future scenario in which fear of travel and an increase in ‘virtual mobility’ makes physical mobility less necessary and/or appealing. For higher education institutions (HEIs), this will mean the loss of income from physically mobile international students (ie, those doing a full degree, exchange year or course in country), which has been shown to be a significant loss to university income streams, as well as increased competition to attract internationally mobile students.

However, this scenario does open up avenues for new income from virtual mobility, ie by introducing or increasing the number of TNE opportunities. Such a shift would potentially challenge the existing thinking around university competitiveness, whereby those who are perhaps less well-known generally but show strength in their digital education offer could become competitive players in the future (not always the same).

2. Student mobility rebounds quickly then grows at pace.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, it is possible that we will see rapid recovery and growth following the pandemic. While the ‘digital turn’ has shown to have positive effects, there is also recognition that digital cannot (always) replace in-person interactions, particularly for the international ‘experience’.

The absence of foreign travel and over-reliance upon digital interactions during the pandemic may mean that student mobility could recover swiftly once regulations ease, and may then continue the strong growth that was projected for the sector before the pandemic. In this case, HEIs will again be competing for physical students as the primary business model, though the digital turn may mean new opportunities to supplement this with a digital TNE offer.

3. Student mobility recovers slowly.

Between these two extremes sit many other possible scenarios, one being that student mobility recovers, but gradually over time as the world turns to the ‘new normal’. Some initial nervousness around studying abroad and availability of digital alternatives could mean a slower pace of recovery for international student mobility, which increases gradually over time as the desire for in-person interactions and experiences abroad increases.

In this scenario, the most successful universities will be those that can provide a strong digital/TNE offer in the short term, paralleled by ensuring they are competitive in attracting physically mobile students in the medium and long term, perhaps looking at hybrid models that offer opportunities for in-person interaction alongside remote learning. This scenario will perhaps be the most challenging for universities to adjust to, as it will require competitiveness for both physical and digital student offers.

Many possible scenarios

These are just three possible options we foresee for the sector, but there are many other alternatives that could become reality. Universities need to be prepared for many possible scenarios and be ready to adapt and update their plans to meet the changing environment. What is true, however, is that digital technology in higher education is here to stay, at least in some capacity, even for international education. Higher education institutions that learn to use it effectively are likely to be the biggest winners in a post-pandemic world.